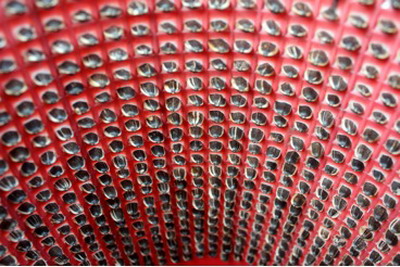

李永庚 Li Yonggeng,填空(局部)Filling the Gaps (Detail),瓜子、塑料 Melon seeds and plastic,30 × 30 × 30 cm,2012

致劳动节——非典型劳动者的劳动典型

Press Release: “To Labor Day: The Fruits of Unconventional Labor”

参展艺术家:光旭、韩五洲、李永庚

Artists: Guangxu, Han Wuzhou, Li Yonggeng

展览时间:2012年4月27日—5月26日

Duration: April 27th — May 26th, 2012

展览地点:798艺术区东街星空间画廊

Address: Star Gallery, East Street, 798 Art Zone

“我赋予众多有形的东西一些价值,即是创作⋯⋯并不只是为了思考。然而为了延伸思考,经由巧妙的双手之劳动力——这些原始的方法会感动在场观众的心灵,穿越比较难以忍受的人类痛楚——疾病、战争、集中营等等。我并不为那些象征而工作。”—博伊斯

光旭、韩五洲和李永庚这三位艺术家的创作都有点“妙手偶得”的意味。虽然没有接受过正规的学院教育,也没有踏出过国门,甚至跟同辈艺术家之间的艺术交流也谈不上密集,他们的作品却天然地呈现出发端于六七十年代西方观念艺术的气质。但这种看上去泊来的视觉效果关联的是一种本土经验:他们分别选取了随手可得的劳动工具、工业材料和现成日用品为创作材料,在对这些材料的塑造中凝聚了自身情感,而他们日复一日足不出户地创作方式堪称为劳动典型。

这三位艺术家都生活在首都的城乡结合部。在这样一种极富中国特色的地段里,既可以看到生活在最底层的劳动人民,与他们生活水准相配套的大型农贸市场、成片的小饭馆,看到毫不讲究的脏乱差、路边摊、随意倾倒的垃圾和大中小型废品收购站,同时也可以看到它与城市生活的连通:扬沙的土路上时不时会闪现出一辆高级车;一些先富起来的人住进了门禁森严的气派院落。艺术家选择这样一种地段工作多数是出于租金和空间的考虑,但这种扑面而来的生活体验也为他们的创作带来影响。 一方面他们可以很便利地从这样的环境里就地取材,一方面这种混搭人文风光所包含着的不连贯、多层次和超现实感也都深入地显现在他们的作品当中。

光旭的作品都像是玩出来的。在他工作室里随处可以找到让人会心一笑的玩意儿:棉花团以一副莫名奇妙的姿态趴在墙壁上,用铁粉制成的皮草围巾从屋顶上耷拉下来,还有直至近看才会大呼上当的木头做的骨头。这些玩意儿以幽默的方式在极简主义的秩序和似真非真的混乱之间寻找到了一种平衡。这些看似轻松的作品从产生想法到完成制作,背后凝聚着很大的劳动量。光旭的动手能力很强,每一件作品都是他自己亲手完成。 这一方面是出于艺术家的偏执,对制作环节高标准严要求,更主要的是,实践这种密集劳动的过程,对他自身是一种极为重要的重塑自我的体验。铁粉系列始于艺术家儿时用磁铁在沙子里玩耍的经历,以及他对工人劳作等生活细节观察后所获得的经验。艺术家利用磁力原理,将它做成具有一定规则的有机的形状,就好像是皮毛和内脏。这两种截然相反的物质属性被综合在一起,构成了一种似真非真的新的有机体。坚硬如铁,却又形随身变。

在韩五洲跳跃性的谈话中,他时不时提及托尔斯泰,或者把“上帝说要有光”这样启示性的句子挂在嘴边。但真正影响他的是在他老家流传甚广的豫剧《十八扯》。五洲说起这种把各种不相干的东西杂糅在一起的艺术形式时简直有些眉飞色舞。这种传统戏剧的形式使他认识到在艺术的范畴里,一切可能都是成立的。于是他走上了艺术之路,因为在他看来,这是唯一可以让他拥有最大自由度的工作。五洲的作品充满了自由的表达,目前已经比较成型的两个系列是用视觉艺术的形式来表现光和声音。他对朴素的东西有种执着的情感。在他使用的材料里,有已经快被社会淘汰掉的手电筒,还带有生活味道用过的塑料袋,普通的劳动工具、废旧的沙发等。五洲对这些平凡之物的艺术改造是一种升华。比如《PIANO E FORTE》,他把锄头和铁镐的木质手柄与金属头部分离开来,仿照古代编钟的形式制作成一件高雅的乐器。作品保留了劳动工具原本的形状和颜色,让人们重新审视其物的美感。而原本被击打的石头被用来反敲劳动工具演奏出音乐,也体现出运用逆向思维的智慧。

李永庚常用the the之名做作品,关于这个名字的由来,他解释说是因为自己喜欢的国外乐队大多以the开头。他对西方文化的感知就好像他起这个名字一样,充满了误读后完全个人化的解读。他的艺术养分和时下热门的类型十分不同,早年卖打口带的经历,让他从摇滚乐中寻找到精神性。而在他后来的阅读中,受教于博伊斯的做事态度和杜尚的生活态度。此外,他还跟我分享了他喜欢的大地艺术。他做创作的出发点,源于最朴实的想法——“家是世界上最温暖的地方”。十五年来,从广州到北京,他以“做家”自居,用自己使用过的日用品做创作,将自己的个人经历与情感注入日常劳作中。 如果说这种实践最初来源于他对物的情感,做着做着这种初衷已经发展为一种思想——通过情感,建立规则。每一件物品都保留有他使用过的痕迹,通过他不按常理出牌的结合方式,建立起新的秩序。与时下大动干戈或者渐趋工艺化倾向的装置艺术相比,the the追求一种即兴的、极简的、禅意的组合。

这三个艺术家都注重在平凡和日常的生活中发现辉煌。他们的艺术实践虽然还更多出于直觉和天赋,但在日积月累的劳动中,他们正逐渐摸索出自己的表达方式和创作脉络。希望这个展览可以鼓励和激发他们的创作,同时我们也尽量抛开语言和现成学术规范的包袱,发现和展示有才华的艺术家的创造,让他们的内省和我们参与其中的思考能够带给其他观众启发性的体验,让每一个观众体味这种艺术的思维方式,重新审视近在眼前最普通的物。

“I endow a number of tangible things with value; that is the nature of creating...it is not just for thinking’s sake. However to extend thought, through the labor of two ingenious hands—such a primitive method can move in the hearts of the audience, and cut through the more unbearable moments of human pain—sickness, war, concentration camps. I am not working for the sake of symbols.”

——Joseph Beuys

The works of artists Guangxu, Han Wuzhou and Li Yonggeng all contain a hint of virtuoso genius, when in fact none of them have received any formal education or stepped foot outside of China. What’s more their exchanges with other artists of their generation are far from numerous. Their works appear to be a natural departure from the artistic temperament of conceptual art in the West during the sixties and seventies, but while this visual effect seems to have stopped over from a different time and place, it is actually homegrown and connected to local experiences. Each of these artists selects their media from whatever commodities and work tools are readily available, and in the process of shaping and re-shaping these objects each consolidates and condenses his own emotional life. This is a creative method based in consistent effort, day-in and day-out—in resignation to a stay-at-home lifestyle. It is deserving of the title of true “labor.”

These three artists all live in the capital’s urban-rural fringe. Places like these are rich with ‘Chinese characteristics’; one can find workers at the lowest rungs of society whose standard of living centers on a farmer’s economy. One can find hole-in-the-wall, forgettable restaurants, and accumulating messes unabashedly left unattended. There are street vendors, trails of garbage strewn casually across store entrances, scrap yards of all shapes and sizes. But then there are also the visible connections to city life: from time to time a luxury car will flash past through a cloud of dust on a dirt road, or members of the nouveau riche will move into an imposing courtyard guarded by high security. The choice on the part of these artists to live in a place like this comes mostly out of practical considerations: rent and space. But what they absorb along the way ends up having a tangible impact on their creations. On the one hand, they can conveniently make use of local materials, on the other hand, the kind of mashup of humanity which constitutes their environment contains a sort of incoherence that is both multi-layered and surreal and that in turn is deeply present in their works.

Guangxu's works are born out of play. In every corner of his workshop there is some little toy, gadget, or oddity that would make anyone chuckle to himself: a large wad of cotton lies against the wall in a baffling posture, a fur-like cloth that is actually made of iron threads droops from the ceiling, upon close inspection bones reveal that they are in fact only made of wood. These playthings seek and in turn achieve a kind of balance between a minimalist order and the chaos of what seems, but is not, real. Guangxu’s works, though seemingly light-hearted and simple, require a staggering amount of time and physical labor in the process from an initial idea to a material result. Guangxu's hands are strong, and he uses them and them alone to complete everyone one of his works. This is in part due to his particular brand of artist's paranoia—his high standards and tight grip on each phase of production—but more importantly the labor-intensive practice is, to him, a crucial process of re-modeling and re-sculpting the self. The artist’s iron-based series grows out of his memories as a young boy playing around with magnets in the sand, and understandings he internalized by watching the minute details of the daily lives of workers and others. Guangxu applies the laws of magnetics and converts them into organic shapes that are guided by specific principles and look as if they are indeed fur or viscera. Metal and viscera: two diametrically opposed materials, and integrated as they are constitute a new kind of near-real organism. Hard as iron, flexible and mutable as organic matter.

Han Wuzhou’s animated conversation style bounces from topic to topic; one moment he will call upon Tolstoy, the next revelatory sentences like "God said, let their be light" will hang from the corners of his mouth. But what truly impacted him is the Yuju Opera (Henan Opera) "Shiba Che," which was popular in his hometown. Han's art—his way of intermingling a whole host of unrelated elements—seems at times to give off an energy of utter rapture and exultation. Traditional opera as an art form is what informed his belief that within the scope of art, one can build any possibility. He chose art as his path, because in his view it was the only work that could give him this degree of freedom. Han's works are brimming with free-form expression; currently his two series that are more fully formed use visual art forms to express light and sound. Han has a persevering emotional connection to what is simple and elemental; among materials he uses are an abandoned flashlight, a plastic bag still ripe with the flavors of what it was once used to contain, ordinary work tools, and a discarded sofa. In his artistic transformation of commonplace objects, he effects a kind of sublimation. For instance, with Piano E Forte he disassembles the wooden handles and metal heads of a wooden hoe and a pickaxe, fashioning an elegant musical instrument modeled after the shape of an ancient tuned bell. The work retains the original shapes and color of working tools, compelling us to re-examine their beauty as objects. What was originally a stone meant to be struck now strikes back, playing would-be tools to create music: an embodiment of the wisdom inherent in reverse thinking.

Li Yonggeng often uses the appellation "the the" in his works; when asked to explain why, he says that it is because he likes foreign band names that start with the word "the." His over-all perception of western culture follows suit: it is a wholly personal reading, arising out of a full-blown mis-reading. The elements that nurture and foster his art are quite divergent from the what is popular at the moment; Li’s experience in his younger years selling “Dakou” cassette tapes—tapes dumped by the West, intended to be recycled, but instead smuggled into China—led him to a pursuit of spirituality through rock music, while later on, he was educated through reading- taught by Beuys' attitude about doing and Duchamp's attitude about living. In addition, he was kind enough to share with me his favorite land art. According to Li, his creative point of departure begins with the simplest idea: ‘Home is the warmest place in the world.’ For fifteen years, from Guangzhou to Beijing, he has been a self-styled "homemaker," working with everyday commodities and tools that he himself has used in the past, and pouring his personal experiences and emotions into everyday labor. If it can be said that his artistic practice takes its earliest origins from his emotional attachment to things, then the philosophy of ‘doing by doing’ has already become a sort of ideology, by which, through emotion, a set of principles can be established. Each item Li uses retains traces of its prior use, and through his builder bag of tricks he casts away common sense and establishes a new order. An alternative to installation art that picks a fight with the times or turns retrospectively towards traditional handicrafts, Li’s work pursues a lively combination of improvisation, minimalism, and meditation.

These three artists all care most about uncovering and unleashing the brilliance of the ordinary and everyday. Though their artistic practices are primarily a product of intuition and natural skill, through their strenuous ‘labor’ practices they gradually amass and hone their own expressive modes and creative frameworks. We hope this exhibition will encourage and further inspire their creativity, while simultaneously giving viewers a chance to appreciate their way of thinking—to re-experience the most ordinary objects imaginable as unimaginably extraordinary.

媒体垂询请联络:

星空间公共事务部媒体专员

孟玥辰

电话:(010)5978 9224

传真:(010)5978 9174

邮箱:pr@stargallery.cn

For inquiries please contact:

Public Affairs Dept. of Star Gallery Media Specialist

Meng Yuechen

Tel: (010)5978 9227

Fax: (010)5978 9174

Email:pr@stargallery.cn

![[北京]时代美术馆“楼上的青年: 2010青年批评家提名展”](attachment/100601/48ac4fdc6c.jpg)