杜尚作品 自行车轮 1913

(译者:在这部分文字中,紧接着对自然和艺术关系的讨论,作者将康德对审美的认识与杜尚的主观审美联系在一起,但同时也否定了新媒体艺术模仿这一范例的创作方式。实际上,作者对整个20世纪60年代前后兴起的新媒体艺术的审美,还是受到了后现代理论环境的限制。这在笔者一些文章中会有进一步的讨论。但他的观点代表了很大一部分处于新媒体艺术前沿的艺术家和理论家的思路,所以很有参考价值。在下一篇文章中,我们还将看到作者对新媒体时代的新艺术形式的讨论。)

现成品

当马歇尔.杜尚把现成的物品拿来当做艺术作品时,他已经从康德的观点中得出了一个极端的结论:创作并不重要,因为观众始终会自己进入审美的过程中。

杜尚的做法有时候被认为是在向崇高致敬,是来自艺术家自发冲动的创作。但是,他所说的“其实,是观众在画画”,却将我们导向另一种解读。杜尚对物品的选择非常谨慎,也非常明智。不论从他自己的解释,还是从物品本身来看,他所选择的都是非常普通,而且“中立”的物品,比如一本课本(译者:课本在中国的观众看来也许不够中立),衣帽架,自行车轮,瓶架,雪铲,塑料桶,咖啡磨以及打印机的罩子。

杜尚说:“选择一个物品是非常困难的,因为过不了几个星期,你就开始喜欢或者讨厌它。你观察这些东西的时候必须抱着漠不关心的态度,放弃所有审美的情感。因为对现成品的选择必须基于视觉上的无动于衷,而且没有好或者坏这些品味存在的余地。”

在许多哲学的讨论中,椅子和桌子常常代表了“客体”本身。而杜尚的现成品也是可以随意替换的,只要是任何没有特别属性,不破坏统一感的物体,都可以在作品中使用。(在杜尚所有的现成品中,架子和容器的大量存在确实可以带来另一个层面的解读:应该悬挂在这些架子上,或者被容器所盛的物体都不存在,于是这些架子和容器成为了“装空间的物体”。)

杜尚认为,任何物体都能够引发审美的乐趣。审美感知并不一定和艺术的背景联系在一起,它的起源与合理性都只存在于观众一方,并且适用于任何一个物体。

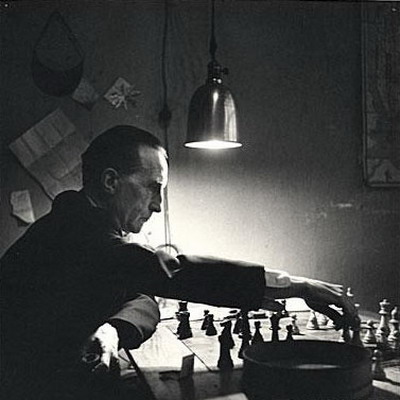

正在下棋的杜尚 1952

随便什么都可以吗

当代艺术理论家迪弗(Thierry De Duve)写了一篇论文叫做“杜尚之后的康德”(1996),他对杜尚的主观艺术态度做了最极端的理解,那就是创作某一件艺术品,而不创作另外一件,是毫无意义的;或者说,创作任何艺术品都是毫无意义的。艺术家必须是“随便做什么都可以的”。

在一段时间中,杜尚看起来是唯一一个采取这种姿态的艺术家,是一个独立的另类。但是很快,在抽象表现主义出现以后,一些艺术流派的出现都在某种程度上受到了杜尚的影响:激浪派,波普艺术,新现实主义,机会艺术,观念艺术。许多艺术家开始使用现成品和大众媒体的图像。许多作品都意在指出现实世界审美的多样性和艺术的不确定性,这些作品常常是刻意甚至可笑的,它们使用了倒置的木桩,空空的木桩,空罐头,镜子,单色,同义反复,荒谬,安静,空格子,空房间……

我们发现,与杜尚的作品不同,这些作品并没有引发对物品的审美,相反,只是表达出了创作的意图。这些作品其实已经站到了康德的审美的对立面:它们不过是一些文艺腔的宣言,带着古怪的说教,完整的定义,以及贫弱的思想。因为,一旦杜尚表达出了自己的观点,对这一观点的重复和发展都显得毫无意义。这样的作品只能成为自我否定的演讲,为它们赖以生存的阐述画上句号。

就像约翰.凯奇的短句:“我在这里 / , / 没什么好说的了 / , / …” (译者:约翰.凯奇是20世纪60年代活跃在实验音乐和行为艺术领域的艺术家。)对随便什么东西的审美很简单,它只不过是一种充满情调的生活方式,而不是艺术。

作者:雷姆科.沙 (Remko Scha) 翻译:许晟

When Marcel Duchamp assigned the status of artwork to existing readymade objects, he drew a radical consequence from Kant’s point of view: that the input doesn’t matter, as long as the observer’s process of aesthetic reflection can take its course.

Duchamp’s gesture is sometimes interpreted as a celebration of the sublime, autonomous, creative power of the artist’s Kunstwollen, but his statement “The spectator makes the picture” suggests a different interpretation. Duchamp chose his objects very carefully, but one should not be mistaken about the nature of his judiciousness. He has made quite explicit statements about this, and one can also read it off the objects themselves. They are very ordinary, “neutral” objects, such as a schoolbook, coat rack, hat rack, bicycle wheel, bottle rack, snow-shovel, plastic bucket, coffee grinder, and typewriter cover.

Duchamp: “It is very difficult to choose an object, because after a few weeks you start to like it or to hate it. You must approach a thing with indifference, as if you have no aesthetic emotion. The choice of readymades is always based on visual indifference and, at the same time, on the complete absence of good or bad taste.”

Like the chairs and tables which always represent “the object” in philosophical discussions, Duchamp’s readymades are “free variables”, where all other objects might be substituted, lacking specific properties which would block unification. (The relatively large number of racks and containers among Duchamp’s readymades do support another level of interpretation: evoking their absent pendants and fillers, they symbolize their own status as “placeholders” in a self-referential way.)

Duchamp asserts the aesthetic interpretation of everything. Aesthetic perception is not tied to the art context – it has its origin and its justification in the observer, and can applied to arbitrary material.

N’importe quoi

To embrace the radically subjectivist aesthetics of Thierry De Duve’s Kant after Duchamp (1996) is to lose any reason to make one particular artwork rather than another, or to make any artwork at all. The artist must do “no matter what.” For a long time, Duchamp seemed to be the only artist taking this stance; an isolated singularity. But in the early 1960s, after abstract expressionism, several artistic schools emerged which in some sense followed Duchamp’s paradigm: Fluxus, Pop Art, Nouveau Realisme, Nul, Chance Art, Concept Art. Many artists started to employ readymade objects and mass-media images. And many pieces were made to illustrate or propound the aesthetic viability of the real world and the superfluousness of art in an explicit, sometimes humorous way in inverted socles, empty socles, glass panes, mirrors, monochromes, tautologies, paradoxes, silence, empty frames, and empty rooms. Note that such artworks, in fact, do not practice the aesthetic interpretation of everything. Rather, they represent the idea of doing that. They are the opposite of a Kantian art: they are statements with a literal meaning, curiously didactic, well-defined, and sterile because, once the point has been made, there is no reason to repeat it and no way to develop it. Such artworks are self-defeating speech acts which close off the discourse that spawned them.

John Cage: I am here / , / and there is nothing to say / , / . . ..

The aesthetic interpretation of everything is a mindful way of life which does not need art.